Target 4.A – Education facilities and learning environments

Key Messages

- The global indicator for target 4.a spans several dimensions, making it difficult to give a quick snapshot of a country’s school infrastructure situation.

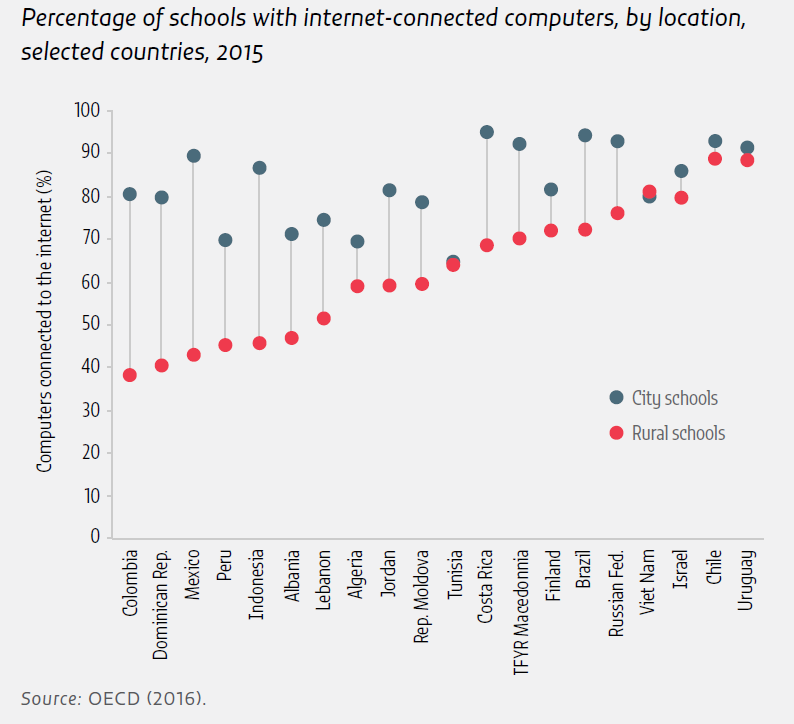

- In sub-Saharan Africa, only 22% of primary schools have electricity. Within-county disparity in access to technology can be large. The percentage of computers connected to the internet is twice as high in city schools as in rural areas in Colombia and the Dominican Republic.

- In half of 148 countries, less than three-quarters of primary schools had access to drinking water. In Mexico, 19% of the poorest grade 3 students, but 84% of the richest, attended schools with adequate water and sanitation.

- Schools surveys show that infrastructure shortages often hinder learning in countries at all income levels, particularly in disadvantaged schools. In 2015, about 40% of principals in Indonesia and Jordan and 25% to 30% in Israel and Italy reported that infrastructure problems significantly hampered instruction. In Turkey, 4% of principals in schools serving better-off populations, but 69% in those serving disadvantaged populations, reported such problems.

- There has been a sharp uptick in attacks on schools since 2004, disproportionately affecting Southern Asia, Northern Africa and Western Asia.

- In Nigeria, at least 611 teachers were deliberately killed and 19,000 forced to flee between 2009 and 2015. By 2016, the Syrian Arab Republic had lost more than one-quarter of its schools.

- Addressing school-related gender-based violence requires a multilevel approach, including effective laws and policies, curricula and learning materials, extracurricular activities, educator training, partnerships between education and other sectors, and monitoring and evaluation.

- National laws and policies must show that violent behaviour cannot be tolerated. Teacher codes of conduct should explicitly refer to violence and abuse and ensure that penalties are clear and consistent with children’s legal rights and protections.

School infrastructure is complex to assess because of the many dimensions involved. However, school surveys found that the state of physical infrastructure often impeded instruction in countries of all income levels, particularly in socio-economically disadvantaged schools. The 2013 Third Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study in Latin America showed that more than four-fifths of the richest grade 3 students attended schools with adequate water and sanitation facilities, while only one-third of the poorest students did.

Primary schools in many poorer countries lack access to electricity. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 22% of primary schools have electricity. Disparity also exists in technology and internet access among and within countries, with rural schools less likely to be connected than urban schools (Figure 15).

Primary school access to drinking water was below 75% in 72 of 148 countries. Access to basic sanitation facilities was below 50% in 24 of 137 countries, including 17 in sub-Saharan Africa.

Learners with disabilities continue to face obstacles, such as lack of mobility equipment, inappropriately designed buildings, absence of teaching aids and unsuitable curricula. In countries including Serbia, South Africa and Turkey, over 35% of schools are affected by resource shortages.

There has been a sharp uptick in attacks on schools since 2004, disproportionately affecting Southern Asia, and Northern Africa and Western Asia. Between 2005 and 2015, armies and armed groups in at least 26 countries used educational institutions for military purposes.

ADDRESSING SCHOOL-RELATED GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE IS CRITICAL

Addressing school-related gender-based violence requires effective laws and policies, appropriate curricula and learning materials, training and support for educators, partnerships between the education sector and other actors, and monitoring and evaluation.

Countries need to adopt legislative frameworks that explicitly protect students from adult-to-child and peer-topeer violence and promote accountability. Chile, Fiji, Finland, Peru and Sweden are among countries that have introduced legislation specifically referencing violence in school. Codes of conduct for teachers need to explicitly refer to violence and abuse and clearly stipulate penalties consistent with legal frameworks.

Laws and policies do not always translate into practice. Many countries fail to implement policies, allocate sufficient resources or ensure support from key actors, such as the police. Too often, local actors lack awareness of rights and obligations. Reporting mechanisms must be seen as reliable and ensure victim confidentiality. Educators should be trained to listen to, support and help students report incidents. After training in Malawi, teacher awareness of school-based sexual harassment increased from 30% to 80% regarding girl victims and 26% to 64% regarding boys. Yet school staff are often poorly prepared to act. In the United States, less than one-third of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual or intersex students who reported incidents of victimization said staff had effectively addressed the problem.

Sexuality education addressing sexual diversity and gender identity/expression can improve school climate, as in the Netherlands. Often, sex education programmes fail to go beyond sexual and reproductive health to deal with gender dynamics.

Educational programmes that promote critical reflection among boys and young men on gender behaviours and norms, including in India, have yielded promising results in improving understanding and attitudes and reducing incidents of violence. Extracurricular activities, such as school-based clubs and sports, can complement classroom instruction to impart positive messages about gender.

Between 2005 and 2015, armies and armed groups in at least 26 countries used educational institutions for military purposes

See previous year’s report on Target 4.a