Accountable governments

Key Messages

- Accountability starts with governments, which are the primary duty bearers of the right to education.

- Citizens can use elections to hold governments to account, but only 45% of elections were free and fair between 2001 and 2011. And politicians often focus more on visible promises, such as school infrastructure, than on less tangible ones, such as teacher professional development.

- Social movements put pressure on government. Anti-corruption protests related to public services accounted for 17% of protests in 84 countries over 2006-2013.

- The media plays a key role in investigating and reporting wrongdoing. In Uganda, a decrease in distance of 2.2 km to a newspaper outlet increased the share of funding that reached a school by nearly 10 percentage points.

- Teachers’ unions can hold the government to account for education reforms. Yet 60% of unions in 50 countries reported never or rarely having been consulted on issues such as the development and selection of teaching materials.

- The basis for accountability is a credible education plan with clear targets that allocates resources through transparent budgets that can be tracked and queried.

- Policy processes must be open to broad and meaningful consultation. In Brazil, about 3.5 million people participated in the national education plan consultation.

- Legislatures have oversight roles but their capacity to enforce is often weak. In Bangladesh, there was an average delay of 5 years before government agencies responded to audit observations on primary education and 10 years on secondary.

- Internal and external audits are essential to limit waste, misallocation and corruption. Civil society support can be crucial. In the Philippines, volunteers textbook delivery points, helping reduce costs by two-thirds and procurement time by half.

- Ombudsman offices help investigate complaints against government. The ombudsman offices in Latin America from 1982 to 2011 helped increase access to education, despite a lack of sanctioning power.

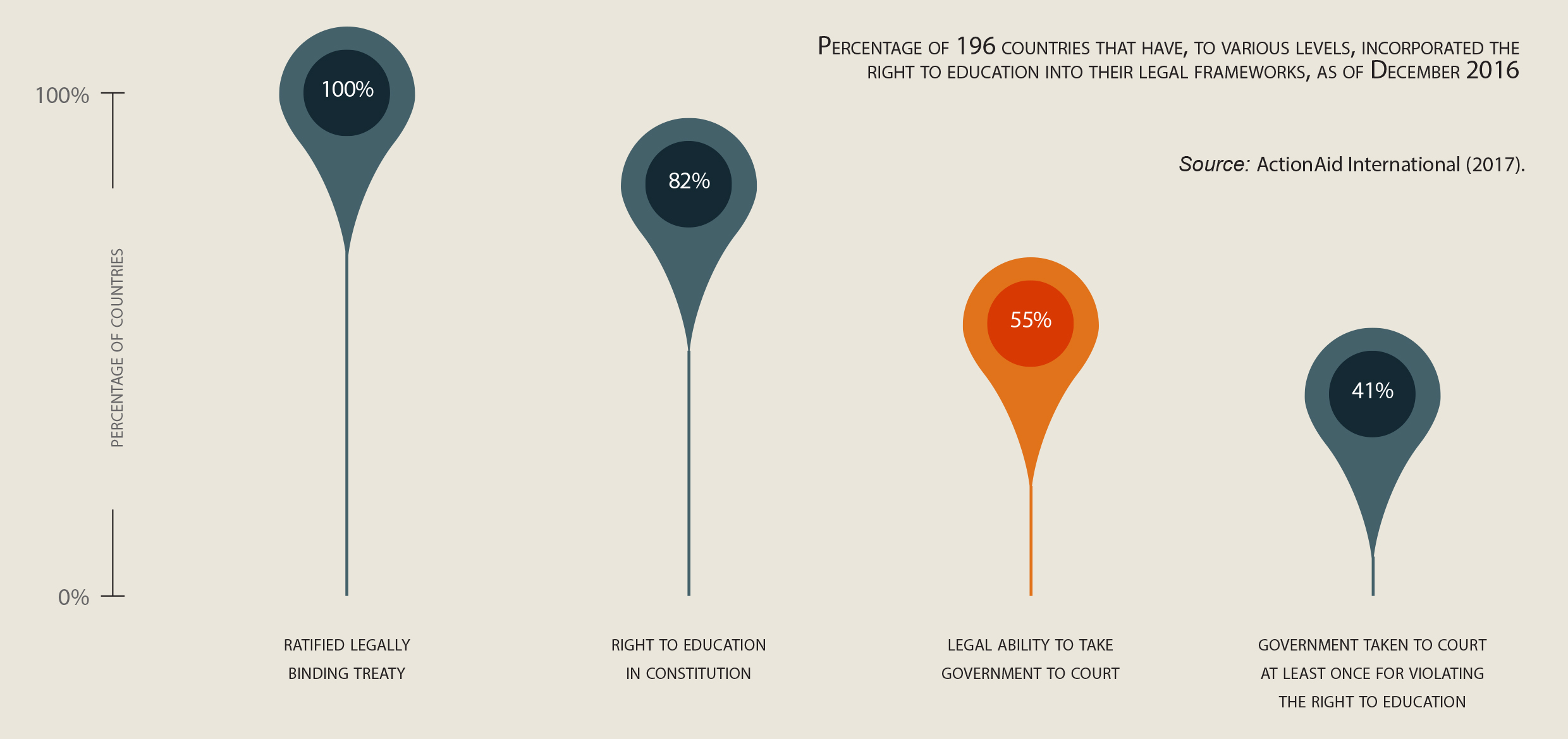

- Citizens can take the government to court for violating the right to education in only 55% of countries. This ability has been exercised in 41% of countries, with effects on school meal provision in India, pre-school funding in Argentina and school infrastructure in South Africa.

- While national education monitoring reports are essential for communicating progress against commitments, governments in only 108 of 209 countries produced such reports between 2010 and 2016. Only one in six countries did so annually.

Governments are ultimately responsible for progress on the global education goals. In poor and wealthy countries alike, governments are held accountable for education commitments, plans, implementation and outcomes.

GOVERNMENTS HAVE LEGAL RESPONSIBILITIES FOR EDUCATION

All countries have ratified at least one legally binding international treaty addressing the right to education. Governments have a responsibility to respect, protect and fulfil this right. Currently, 82% of national constitutions contain a provision on the right to education. In just over half of countries, the right is justiciable, giving citizens the legal ability to take government to court for violations (Figure 2).

INTERNATIONAL REPORTING PROCESSES HAVE VARYING EFFECTS ON GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTABILITY

Countries that have ratified any of the seven core United Nations human rights treaties pertinent to education must report periodically on measures taken to meet obligations. One of the seven core treaties is the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which calls for the development of an inclusive system at all levels of education. It promotes a rights-based approach to education for people with disabilities, providing a solid basis for government accountability. The CRPD provides for the creation of international and national implementation and monitoring mechanisms. Countries must collect data and report to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

While most of the 86 country submissions to date report that constitutions, laws or policies explicitly refer to the right of people with disabilities to education, few define disability. Lack of a clear international definition can make it harder to develop programmes and comply with international standards. Similarly, 42 countries’ constitutions, laws or policies explicitly refer to inclusive education, suggesting a trend away from special schools in favour of inclusive programmes in regular schools. However, policy does not always match practice.

Parallel reporting by non-government organizations (NGOs) can influence the conclusions of United Nations human rights treaty committees. For instance, parallel reporting on underfunded public education and unregulated private schools in the Philippines was reflected in committee recommendations.

In 42 out of 86 countries, constitutions, laws or policies explicitly refer to inclusive education

Countries also report on progress towards the SDGs, although this reporting is voluntary. To date, 44 countries have submitted progress reviews. The 2019 United Nations global thematic review, ‘empowering people and ensuring inclusiveness’, will carefully examine SDG 4. The effectiveness of a voluntary, country-led approach to achieving change remains to be seen; lack of external enforcement mechanisms may delay progress.

CITIZENS CAN PRESSURE GOVERNMENT TO KEEP PROMISES THROUGH THE POLITICAL PROCESS

The political process motivates officials to respond to public demands. One mechanism is free and fair elections. Between 1975 and 2011, 469 of 890 elections of national leaders in 169 countries were considered free and fair. The percentage declined from 70% in 1975–1985 to 45% in 2001–2011, partly due to the emergence of elections in young democracies (Figure 3).

Public education spending increases with a shift towards democracy and openness. Still, it is difficult for voters to identify and hold accountable those in elected positions for failed or ineffective education policy. Simple campaign promises can divert attention and investment from more important education issues. Governments tend to focus and deliver on visible education infrastructure more than less tangible education inputs, such as professional development.

Some argue electoral competition spurs responsible action, but the evidence is mixed. In Brazil, mayors facing re-election misappropriated 27% fewer resources than term-limited mayors. By contrast, in the Republic of Korea, switching to direct election of superintendents did not significantly alter education expenditure or rates of completion or enrolment.

CITIZENS CAN ALSO PRESSURE GOVERNMENT THROUGH SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

Elections are not the only political mechanism holding governments to account. Citizen action can also put pressure on government, as in the case of successful student movements for lower university fees in Chile and South Africa.

Civil society organizations (CSOs) use a range of strategies, including legal mechanisms, surveys and other research, open data, coalition building and media campaigns. Argentina’s Civil Association for Equality and Justice took the Buenos Aires city government to court for not responding to access to information requests related to early childhood education.

Surveys collect information that can highlight policy deficiencies and advocate for change. In many countries, including Kenya, Pakistan and Senegal, citizen-led surveys assessing children’s basic reading and arithmetic abilities have been used to pressure government to improve education delivery.

CSO coalitions, such as the Campaign for Popular Education in Bangladesh, have built momentum to increase pressure on government, for instance to increase resources for education. Citizen report cards, first used inBangalore, India, in 1994, have been adopted elsewhere, including Rwanda.

In some countries, including India and the United Republic of Tanzania, CSOs have played an important role in countering corrupt practices by using budget tracking and analysis to monitor government disbursements and expenditure, and in assessing whether resources are allocated and spent in line with budgets and plans.

Disabled people’s organizations participated in monitoring the implementation of the CRPD in 50 of 86 reporting countries

Organizations for people with disabilities can lobby governments for change. NGOs and independent human rights institutions can provide information and raise awareness. Disabled people’s organizations helped monitor CRPD implementation in 50 of the 86 reporting countries but took part in the national review in only 29 countries. Lack of capacity is an obstacle to participation.

Teachers’ unions are part of the broader civil society but also have a distinct voice and role. They can help hold governments accountable by supporting or resisting education reform and promoting dialogue on sensitive issues the government may hesitate to address. Formally including unions in policy-making increases accountability and teacher buy-in while improving union–government relations. Unfortunately, however, unions are not regularly consulted on reform. Of 70 unions in more than 50 countries, over 60% were never or rarely consulted on the development and selection of teaching materials.

Of 70 teacher unions in more than 50 countries, over 60% were never or rarely consulted on teaching materials

THE ROLE OF THE MEDIA IS KEY IN RAISING CRITICAL EDUCATION ISSUES

Citizens need valid information to hold government accountable. The media can serve as a watchdog on the government, helping citizens evaluate its performance. It also serves as a channel for CSOs to disseminate their work and bring issues such as equity to the public agenda. International, national and local media have published results of citizen-led assessments to illustrate the challenge of ensuring basic skills for all children.

The media also reports findings of research by think tanks, universities and government institutions. Increasing media information about how public funds are spent can help empower citizens and increase pressure on education officials to act responsibly. In Uganda, a 2.2 km decrease in distance to a newspaper outlet increased the share of funding that reached a school by nearly 10 percentage points.

While traditional media still plays an important role in explaining complex issues to the public, social media allows users to share information widely, free from editorializing, journalist filtering or, in some cases, government censorship. At a time of often rapid change in education policies, the functions social media can fulfil are important.

Yet the media also needs to be independent, accountable, and able to provide relevant information and reflect diverse social views. Media personnel directly involved in researching, analysing, organizing, and writing or broadcasting the news should have the technical expertise to report on education issues and be trusted.

CREDIBLE EDUCATION PLANS WITH CLEAR LINES OF RESPONSIBILITY ARE IMPORTANT TOOLS

Once governments are sworn into power, their education planning documents facilitate accountability by establishing official commitments and clarifying responsibilities. Governments often set multiyear strategic plans for the education sector, but annual operational plans are usually key to planning and coordination.

Institutional mechanisms granting more formal powers to all stakeholders can strengthen accountability. A joint steering committee of government and non-government stakeholders with formal power to appraise and approve sector plans is recommended. However, where capacity is a challenge, stakeholders may not always represent all constituents.

Governments that assign experts, consultants or donors to draft plans quickly risk undermining local ownership and commitment

Truly participatory education planning can be time consuming. Governments may be tempted to assign experts, consultants or donors to draft plans quickly, avoiding extended consultation. Such shortcuts undermine local ownership and commitment. Aid recipient countries should take care to avoid donor monopolization of planning.

Clearly delineated responsibilities are important, particularly in decentralized systems, where responsibilities are often undefined and overlapping, blurring lines of accountability. Decentralized administrations, especially in low income and fragile countries, often lack capacity for strategic planning.

Using performance-based conditional grants to increase local government capacity and transparency has improved financial management in several low and middle income countries. In the United Republic of Tanzania, authorities meeting minimum conditions for grant eligibility rose from about 50% to 90% within three years.

But mandating strict local accountability for centrally determined outcomes can also have negative consequences. An excessive audit culture can obscure responsibilities, reduce collaboration, undermine innovation and cause service providers to focus on targets rather than improvements.

INCREASED OVERSIGHT DURING BUDGET FORMULATION CAN ENSURE RESOURCE ALLOCATION TO PRIORITY AREAS

Empowering stakeholders to participate in budgeting and review planned expenditure can improve equity in resource allocation. Budget scrutiny is the paramount function of legislatures, requiring time and expert input. CSOs can help them assess proposed budgets and inform deliberations, as in Indonesia and Kenya. Programmatic rather than line-item budgets aid legislators in evaluating expenditure more effectively.

HORIZONTAL ACCOUNTABILITY CAN BE EFFECTIVE

Legislative committees, ombudsman offices and courts are examples of horizontal accountability tools that represent public voices and challenge executive overreach. Internal and external audits are effective budget execution accountability tools and help limit waste, misallocation and corruption. However, they require sufficient capacity.

Legislative committees fulfil a critical monitoring function. Lack of independence, capacity or authority can limit their ability to drive change, but deliberation among legislators with specialized education expertise can improve policy proposals on the less divisive issues. The legislatures of New Zealand, Norway, Peru, the United States and Zambia have permanent education committees which scrutinize government actions, review laws and recommend changes. In the United Kingdom, committee recommendations were identical or similar to government policy measures in 20 of 86 cases, especially in the development of legislation to reform the inspection system.

The legislatures of New Zealand, Norway, Peru, the United States and Zambia have education committees which scrutinize government actions, review laws and recommend changes

Ombudsman offices receive citizens who wish to lodge complaints against government. They are especially important when citizens are uncomfortable engaging with government officials. In 2010, 118 countries had an ombudsman. The office often deals with politically contentious issues, which can put it in conflict with the government. In Latin America, the presence of an ombudsman, even without sanctioning power, helped improve access to education, health and housing from 1982 to 2011. In Indonesia, the ombudsman office was essential in exposing fraud involving tests being sold to students and answers being shared on mobile phones.

CSOs and citizens can strengthen external audits. In Chile and the Republic of Korea, online citizen complaints and suggestions highlight areas for auditor attention. Public expenditure tracking surveys enable CSOs to conduct social audits of expenditure. However, these are often one-off, donor-driven interventions that rarely lead to substantive, lasting changes.

BUILDING AN INSTITUTIONAL CULTURE OF INTEGRITY IS KEY TO TACKLING CORRUPTION

Corruption can occur in all aspects of education provision, from finance and service procurement to institutional accreditation, teacher management, examinations, scholarships, research and textbooks. Whether it involves headline-grabbing misappropriation or entrenched, low-level practices, its repercussions extend well beyond accounting losses, affecting education access and service quality. Corruption biases government resource allocation decisions, reduces productivity and decreases public revenue.

While World Bank studies on leakage in funding transfers from central to local government and thence to schools inspired much of the work in this area, tracking funds to receipt at point of service remains challenging, especially when there are no clear rules for allocations. Non-existent ‘ghost’ teachers and schools constitute a complex and contentious topic. Nigeria had 8,000 allegations of ghost teachers or teachers collecting more than their official salary in the first half of 2016 alone.

After reforms to improve the education equalization fund mechanism in Brazil, inspections by the Comptroller General of the Union in 120 municipalities and 4 states still found that 49 had irregular bidding processes, 28 had irregular contract executions and 21 had ‘cash withdrawals’ out of the account.

Egregious practices may be imperceptible to outside observers and their scale difficult to verify, for instance in challenging circumstances such as conflict settings. About 80% of the 740 schools in Ghor province, Afghanistan, were not operating even though the education department was paying teachers’ salaries.

Some corruption that is too entrenched often goes undetected. In a public expenditure tracking survey in Bangladesh, about 40% of district and subdistrict primary education officers admitted to making ‘speed payments’ to accounts officers for expenditure reimbursement. These payments may not involve actual or direct leakage from the public purse, but they encourage officials to make up the costs in other ways.

Revelation of irregularities is not sufficient, and even legal norms and structures need to be accompanied by improved monitoring mechanisms, including strong and independent audit institutions, open information systems and a facilitating environment for media oversight and NGO involvement. When cases of corruption are uncovered, the police and courts play a crucial role in follow-up.

MONITORING AND EVALUATION OF EDUCATION SHOULD BE SYSTEMATIZED

Monitoring and evaluation can promote government accountability. To be useful, monitoring must report on desired outcomes and data must be accurate and collected regularly. However, monitoring and evaluation systems are often fragmented. Agencies differ in method and frequency of data collection, and data may not be centrally compiled, comparable or accessible.

One way to consolidate information is for governments to prepare national education monitoring reports as part of obligations to bodies such as legislatures or international organizations, and to help citizens hold governments to account. Of 209 countries, 108 have published a national education monitoring report at least once since 2010, but only about 1 in 6 countries worldwide does so regularly.

Of 209 countries, 108 have published a national education monitoring report at least once since 2010, but only about 1 in 6 countries worldwide does so regularly

National education monitoring reports are more common in richer countries, but middle income countries, such as the Dominican Republic and the Republic of Moldova, as well as some low income countries, such as Uganda, also prepare reports. Almost all reports cover primary and secondary education. About three-quarters cover early childhood care and education, two-thirds cover higher education and one-third cover adult education.

Reports differ in their emphasis. About 60% focus primarily on describing actions taken and 25% on assessing the situation, reflecting the accountability concerns associated with various domestic contexts. Reports may also focus on accounting for expenditure. Some, such as Germany’s Bildungsbericht (Education Report), are legally required as part of reporting to the public and generally focus on accounting for actions or expenditure. Panama’s education ministry publishes an annual report as stipulated in the law on transparency in public management. In the Philippines, the ‘transparency seal’ provision of the budget law, ‘to enhance transparency and enforce accountability’, calls on all national government agency official websites to post annual reports for the last three years, in line with precise instructions in the national budget circular.

Some monitoring information may need to be externally commissioned or produced by an institution whose work is respected and widely accepted as free of government control. Over the last decade, autonomous evaluation agencies have been established in Latin American countries including Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico, and their responsibilities have been strengthened either by practice or through new legal provisions. Sustainable funding is a key factor in their ability to play their role effectively.

In aid recipient countries, annual joint sector reviews that bring together government, donors, civil society actors and other stakeholders are now common. However, they have weaknesses, as participation is not broad enough, implementation plans for recommendations are lacking and agendas are often driven by donors.

Of existing national education monitoring reports, only one-third cover adult education